Consider these real-world vignettes:

o A mother is in the midst of an emergency delivery of a baby at a small local hospital. But her baby is born safely because her doctor got real-time guidance by videoconference from an academic medical center more than a hundred miles away.

o A low-income patient in rural Virginia has severe and disfiguring psoriasis. But he can consult with a far-away dermatologist by video about the latest treatments to help restore his function and appearance.

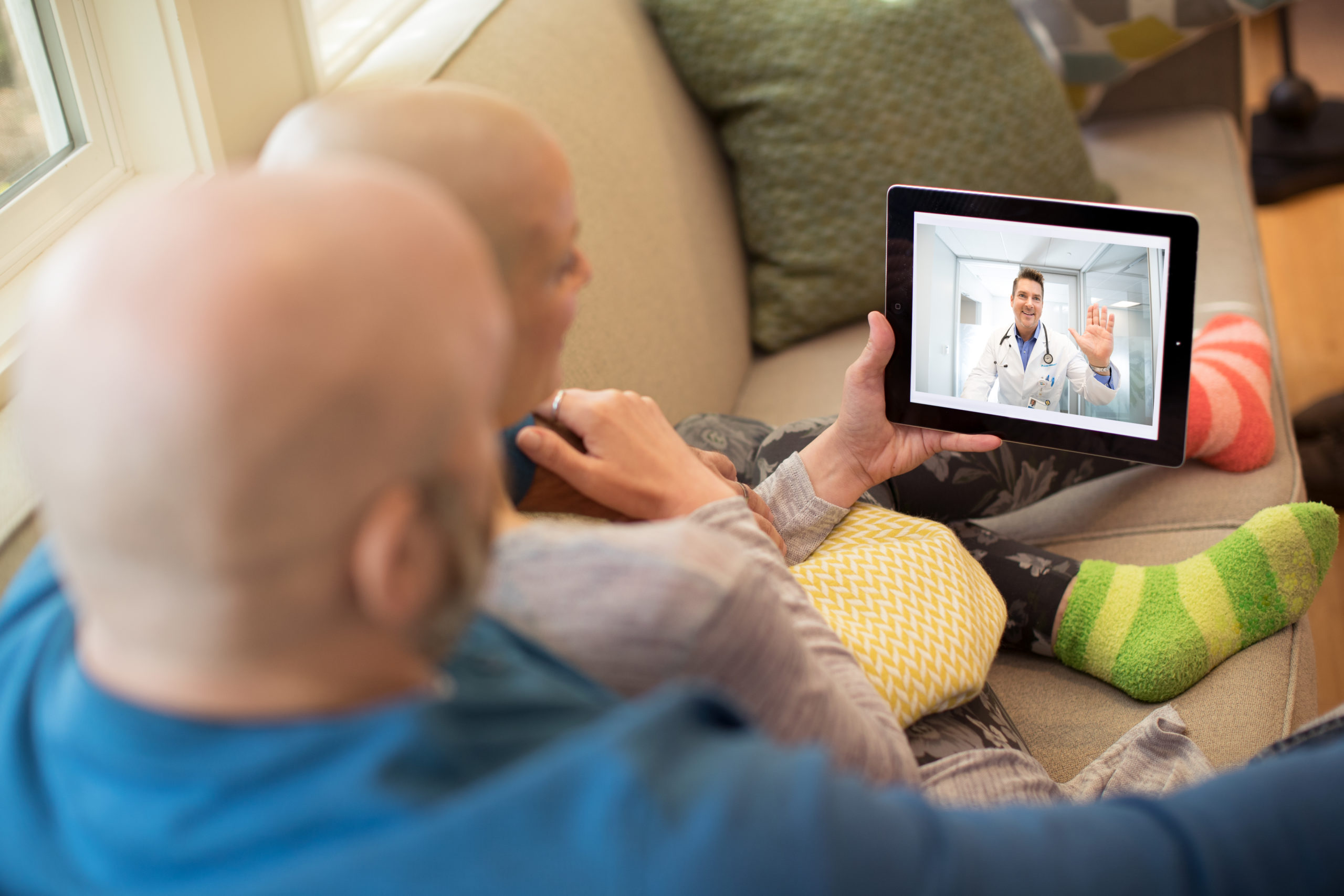

o A cancer patient prepares to start treatment, but then learns via videoconference from an expert at a major cancer center that her cancer was inadvertently misdiagnosed by her local oncologist. As a result, she receives a corrected diagnosis and starts the appropriate regimen.

On one level, these anecdotes tell the story of telemedicine: The ability of patients, and often their local clinicians, to have consultations over distances with other clinical experts who can bring their insights to bear on patient care.

On another level, these stories herald far more: The unleashing of a system of “Health Care Without Walls” that can spread and democratize medical knowledge; meet patients where they are, in their homes, communities, or other locations; focus new attention on the social and economic circumstances in which patients live most of their lives; and defy the conventional boundaries of time and distance to get the right care to the right patient when it is most needed.

So, with all these formidable benefits going for it, why is telemedicine – a decades-old technology – only now beginning to make a dent in the delivery of health care in the United States?

This question and others were discussed at a forum I participated in, entitled “Leveraging Telehealth to Expand Access to High-Quality Care” and hosted by Kaiser Permanente’s Institute for Health Policy (IHP) at the Center for Total Health in Washington, D.C., on December 14. The forum brought together roughly 80 leaders from a variety of settings, including government, academia, advocacy groups, associations, think tanks, and health care providers to discuss the use of telehealth as an integral part of care delivery. Several themes emerged, including the potential impact of telehealth to improve access and quality, to help bend health care’s cost curve, and to address work force issues, such as perceived shortages of physicians. Challenges also surfaced, including the need to train and educate physicians, nurses, pharmacists and other care providers in caring for patients via telehealth; to address limitations on payment and reimbursement; and to fund further research to better understand telehealth’s promise.

As my organization, the Network for Excellence in Health Innovation (NEHI), has discovered in our Health Care Without Walls initiative, the reasons telemedicine is not yet playing a major role in U.S. health care are practically innumerable – and familiar to any serious student of our nation’s health care system and health policy.

A primary concern is cost. There’s no doubt that telemedicine, along with the gradual movement of care outside of hospitals and other conventional institutional settings, has the capacity to reduce costs in the broadest sense – not just to the health care system, but to patients and others. For example, an employee who doesn’t have to leave the work site to consult with a doctor, doing it instead via telemedicine, is an employee who won’t lose hours of productivity in the process. The University of Virginia Medical Center at Charlottesville, which offers telemedicine in 60 specialties and subspecialties, estimates that it has spared patients more than 17 million miles of driving to the medical center to obtain care.

But outside of capitated health systems such as Kaiser Permanente, where fee-for-service and volume-based payment still reigns, payers see telemedicine as a cost add-on. Too often, they say, a telemedicine visit results in a “punt,” where a doctor may interact with a patient via telemedicine then refer the patient for a follow-up visit to a primary care doctor or even send them to a hospital emergency room. The bill from the telemedicine provider is then simply an “extra” added to the overall tab.

Although all state Medicaid agencies now cover some form of telemedicine, similar concerns about payment add-ons have prevented Medicare from fully embracing telemedicine as well. With only a few exceptions, such as a telemedicine waiver available to participants in the Next Generation ACO model, Medicare mainly limits payment for telehealth to rural Health Professional Shortage areas and to services that extend from closely defined “originating sites,” such as physicians’ offices, hospitals, and skilled-nursing facilities.

Unless the entire U.S. health care system moves to full risk-bearing models, so that providers have real incentives to find more efficient modes of care delivery, it’s unlikely payers will change their tune. More payment models that will support telehealth adoption are needed within Medicare and commercial insurance. At NEHI, we’re working to develop proposals to pay for telemedicine as a means of transitioning providers along a kind of glide path toward great risk-bearing payment models.

Regulatory barriers to a greater role for telemedicine also abound. A number of states still bar clinicians from making diagnoses unless a patient is physically present in the physician’s office. And as far as practicing telemedicine across state lines is concerned, fewer than half of states have signed onto the Federation of State Medical Boards’ Interstate Medical Licensure Compact, which creates expedited pathways so physicians can apply for and receive licenses in states where they are not currently licensed – a prerequisite for conducting a lawful telemedicine session with a patient in another state.

These and other barriers – including health system inertia – must be addressed before telemedicine can reach its full potential. To spur a larger pro-adoption movement, however, it may be necessary to create a vision of future health care that supersedes any specific technology, whether telemedicine, remote monitoring, or even robotics. A true system of Health Care Without Walls could constitute more truly universal care that better united individuals, populations, and their care providers in direct pursuit of better health. Who among us could ask for more?